Imagine you are in the year 1919, sitting with the directors of one of America’s most successful companies. Your business is a juggernaut that, in today’s dollars, takes in half a billion annually. The company’s founder has just died, leaving an estate that, again in today’s dollars, is worth $127 million. The company has offices in many of the world’s great cities, and demand for its product has been strong for decades.

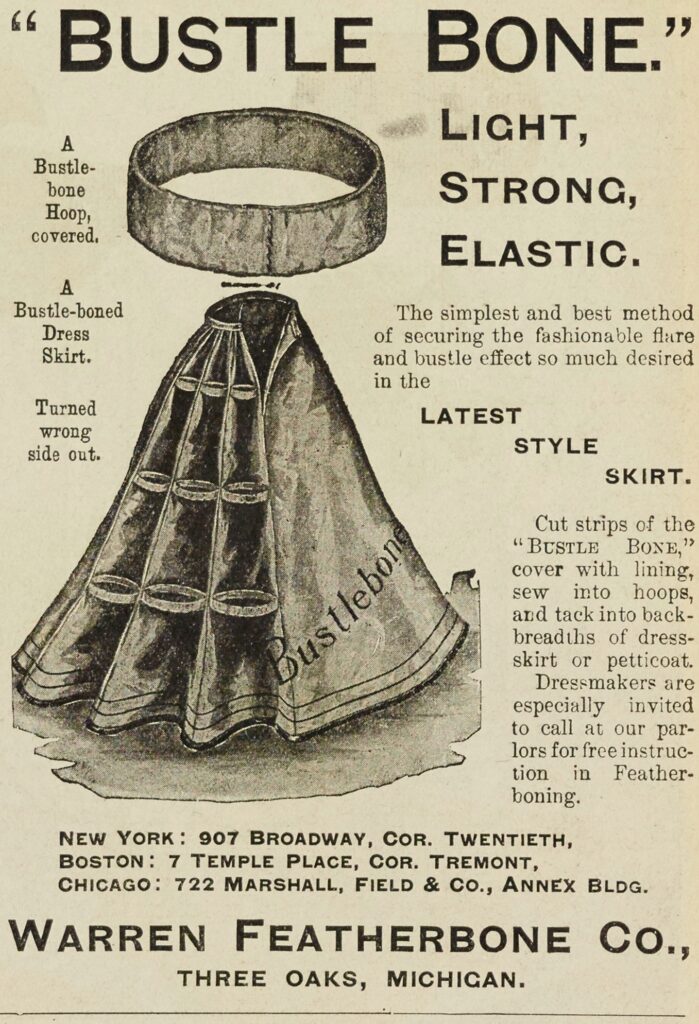

What does this company make? Stays made out of turkey quill feathers that stiffen women’s corsets. Compared with the whalebone that used to go into corsets, this was revolutionary.

Hindsight tells us that the Roaring Twenties didn’t roar loudly at all for The Warren Featherbone Co. once young flappers abandoned corsets, and the girdles that came later didn’t need stiffeners. But you couldn’t have predicted that in 1919. The directors’ bet on fashion styles turned out to be a risky gamble.

In contrast, prospects for construction supply look solid for decades to come. Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies forecast recently that America will need to build roughly 1.4 million new housing units per year from 2025 to 2035 and nearly 1.1 million annually from 2035 to 2045. That 1.4 million annual need exceeds by far the barely 1 million homes we’re putting up this year. It also tops the 1.3 million starts that many groups are predicting for 2025. What’s more, a 1.4 million annual pace won’t dent the shortfall we already have, which the Joint Center estimates at 1.5 million to 5.5 million homes.

Lumber and building material distribution people face a lot of uncertainties in 2025: the economy, immigration, tariffs, and taxes all are what famously have been classified as “known unknowns.” But one thing we can count on is steady, unrelenting demand for new and improved homes. It’s a quality that makes construction supply such an attractive target for investors.

Construction products aren’t like corset stays. Fashion trends come and go, but we all need a roof over our heads.

(Here’s a video about E.K. Warren, the featherbone company’s founder. By the way: The Warren Featherbone Co. did plummet in value during the 1920s. Its other uses for turkey quill feathers kept it in business for many years, but ultimately it changed industries in the 1950s, making baby clothes in Georgia until it closed in 2005.)